In consequence of the digital switchover and the changed user needs brought about by the information revolution and social networking, as well as in the light of the social and market situation, there are few public service media in Europe (or anywhere else in the world) that still have a significant audience today. Public service broadcasting and the provision of public service content is no longer what it used to be in the traditional dual media system, where the national regulatory body could still control the media, which gave prominence to public and private interests. Today, the power that was in the hands of public service broadcasters for decades has shifted from the political actors that set (national) strategies and guidelines and regulate media into the hands of the commercial actors that own social networks and think on a global scale (Bayer 2008), while the untenability and destruction of media that are predominantly based on national regulation has become an issue.

For decades, Norway has stood out among the countries operating a press subsidy system for its ability to maintain a diverse newspaper and magazine market over a period of many decades, despite concentrations of ownership, the rise of tabloidization and the rapid spread of the internet. The ability of Norwegian newspapers and magazines to successfully preserve their position can be attributed to the general perception that society is responsible for the press and for maintaining a diverse range of information, in contrast to the Anglo-Saxon model which emphasises the social responsibility of the press. As part of the notion of the press as a social institution, the press in Norway, regardless of its ownership background, is seen as a channel of public service information rather than primarily as a commercial enterprise. This is the foundation of Europe’s most successful press support system, which is based on a well-developed structure of local/small-community newspapers and a broad social consensus (Antal 2011, 226–227).

This does not mean that the explosive spread of the internet and then social networks has not had devastating consequences in Norway. Norwegian public media had to face one of its biggest challenges in its history. In October 2022, the Norwegian government approved the state budget for 2023 and increased the subsidy for the public broadcaster responsible for operating radio and television channels, the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (Norsk rikskringkasting, NRK), by NOK 86 million (total subsidy of nearly NOK 6.1 billion), yet the public broadcaster starts 2023 with a precedent-setting “savings target” of NOK 300 million and forced to prioritise its future plans.1 In this context, NRK Director General Vibeke Fürst Haugen said in November 2022: For 2023, NRK will receive a tight financial framework, which, together with abnormally high price and cost growth, means tough priorities. […] “It has been challenging to save more than NOK 300 million in next year’s budget. All reductions are made with a view to how we can best protect our important mission, audience use and NRK’s reputation.”2

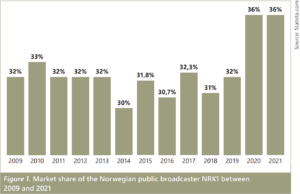

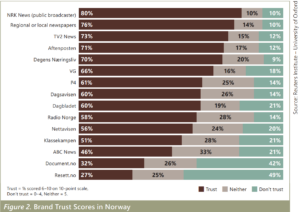

However, the significant cut in NRK’s budget3 is mainly due to economic reasons and not to the loss of popularity of the public broadcaster: the public broadcaster NRK is unprecedentedly still the media organisation with the highest reach and trust among Norwegians. Its television and radio channels lead the market4, and its TV channel NRK1 was the most popular TV channel in Norway in 2021 with an audience share of 36%.5 NRK also operates three national TV channels, several digital radio stations and has a significant online activity. Until 2022, 94 per cent of its funding came from a compulsory licence fee paid by Norwegian TV owners, but from 2023 this will be changed and it is now funded from the state budget through a special tax established for NRK. In any case, despite the restrictions, Norwegian media is still considered the freest in the world; this northern European country also regularly tops the annual Reporters Without Borders (RSF) press freedom index.6

In addition, Norway is the country most often referred to in the literature as the “most connected country” in the world. In July 2022, 98% of the Norwegian population of nearly 5.5 million people, or almost 5.4 million people, were active internet users.7 Facebook is by far the most popular social network, followed by Pinterest and, like in Hungary, Instagram, while “X” (formerly Twitter), which is extremely popular in the US and Western Europe, is one of the least popular social platforms8. Norwegians are also among the most avid newspaper readers in the world: while the readership of printed editions has declined significantly in recent years and subscriptions to online newspapers have increased, statistics show that in practice this only means a shift in readership from paper-based printed publications to online media.9

The government has also introduced various regulations and guidelines to ensure the responsible use of social media. One of these is the so-called Personal Data Act, which has been in force since 20 July 2018 and provides guidelines for multinational social networks on how the personal data of Norwegian citizens should be handled online. This Act outlines requirements for consent, data storage and data sharing, among other things. Norway generally uses EU directives as a basis for national regulation. And this is the case here: with the adoption of the EU’s main data protection law, the General Data Protection Regulation 2017/679 (GDPR), the Norwegian government has repealed Directive 95/46/EC (Data Protection Directive), which was in force until then, resulting in increased – albeit not complete – harmonisation of data protection laws in EU Member States. Although Norway is not an EU Member State, it is part of the European Economic Area (EEA) and therefore the GDPR had to be incorporated into the EEA Agreement before it could be transposed into national legislation.10 In the same way, the Digital Service Act (DSA)11 proposed by the European Commission in December 2020 and adopted by the European Parliament in January 2022, which aims to create a safer and more accountable online environment in the EU Member States, is planned to be integrated into national law as well.

An equally important milestone in the regulation of social networks in Norway is the adoption of the so-called E-Commerce Act. This aims to regulate e-commerce in Norway and to ensure that online transactions are carried out in a transparent and safe manner12, while the Marketing Control Act of 2009 provides guidance on advertising and marketing practices in social media. The latter ensures, among other things, that advertising is not misleading and that products are marketed responsibly within the borders of the country.13 In this context, it is important to mention the recent amendment to the law adopted by the Norwegian government, which is intended to restrict the marketing activities of so-called influencers, i.e. opinion leaders, who market on social networks. This amendment was a high-profile case internationally. The amendment, adopted in the summer of 2022, requires content producers who earned a reputation on social media to flag any photo shared on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or other social networks that has been enhanced with Photoshop or other image editing software to improve the appearance of the body, skin or face. Consequently, failure to indicate that a photo has been edited results in a fine from the summer of 2022.14

It is also important to note that in Norway, hate speech and discrimination are also subject to strict laws, and these laws also cover online platforms. Any content that is deemed discriminatory or incites hatred can therefore be reported and removed immediately under Norwegian law.15 It is also worth briefly mentioning that Norway follows the principle of net neutrality. In practice, this means that internet service providers must treat all data on the internet equally. This ensures that social media platforms are not favoured over other data or content providers.

1. The intertwining of Norwegian public service media and social networks

From the outset, Norway has sought to keep pace with technological developments and place a strong emphasis on the protection of personal data, the promotion of responsible advertising and the prevention of hate speech and discrimination in computer-mediated communication (hereinafter: CMC) and new media, but most notably in mediatised social communication dominated by social networks. With the advent of social networks, however, it was far from clear how the globally recognised and long-established Norwegian public service media could adapt to the new tools (platforms) made available by new media. Disciplines that draw on the social science paradigm consider it an axiom that whenever a new medium emerges, the social public sphere necessarily changes (cf. Habermas 1962, Castells 2005, Bajomi-Lázár 2009, Tóth 2022). This change has also posed new challenges for the Norwegian public service media, as there was no ready concept at the beginning as to whether the media belonging to NRK should use the social networks, which are mainly owned by American multinational corporations. This uncertainty was fuelled by the fact that the current tools available to a democratic state governed by the rule of law provide an extremely narrow framework for controlling the cross-border activities of the US Silicon Valley technology giants.16

In the debate on this issue, Norwegian society is divided into two camps: one that believes that the Norwegian public service media, instead of enthusiastically contributing to the growth and development of US-based multinational companies providing commercial services (Facebook, YouTube or Twitter), should rather spend time and money on developing local alternatives that are not driven by commercial intentions. This argument is supported by the fact that the original task of public service media is to protect democracy, strengthen national identity and cultural-social integration, and maintain a content service that reflects national interests, values and opinions (Antal 2011, 51). In addition to fulfilling the requirements of the democratic political system, i.e. providing balanced and objective information, the most important objectives of public service can therefore be seen in terms of preserving national culture, language and identity (cf. McQuail 2003, 42), and meeting the social and cultural needs of media consumers and preserving cultural heritage. However, no multinational company can – or wants to – meet these criteria.

The other camp, however, argues that it makes sense to reach the audience where the audience itself is (Moe 2013, 116–117). Because like it or not, in recent years Facebook and other social networks have indeed become a social arena where the Norwegian audience spends a lot of time. Thanks to their rapid growth, social networking sites have become an essential part of everyday life in many parts of the world, an inescapable means of everyday communication. This was precisely the original purpose of social networks: to connect people virtually and to provide a space for communication, mediatized communication, from individual to individual and between groups. Over time, social networks have outgrown their initial purpose and are now used by commercial multinational companies, political actors and even extremist groups to convey their (campaign) messages, often in defiance of public service principles and interests.

The Norwegian public service broadcaster has finally decided that social networks are an inescapable platform for social communication, and that the Norwegian Media Authority (Medietilsynet) is responsible for regulating the platforms, as it is for all other media services in Norway. The declared aim of the Media Authority is to promote diversity, quality and the freedom of expression in the Norwegian media. This state-run organization also seeks to ensure that social networking sites in the northern European country comply with the country’s laws and regulations. The Media Authority therefore has a number of rules and guidelines that social networking sites in Norway must follow, in full compliance with EU regulations. An example of good practices is that social networking sites must have efficient mechanisms in place to handle user complaints: they must ensure that their content is not harmful or offensive and measures must be taken to protect children from harmful or inappropriate content.17 Social networking sites must also comply with Norwegian data protection laws, in particular with regard to the collection, storage and use of personal data. In addition, the Media Authority monitors the activities of social networking sites to ensure that they do not violate Norwegian laws, e.g. in relation to hate speech, discrimination or incitement to violence. The authority may also take measures, such as imposing a fine or blocking access to social networking sites if they violate Norwegian laws or regulations.

However, the relationship between the Media Authority and social networks was not so clear-cut in the beginning. To understand the considerations and practical experiences that led a national authority to put US-based multinational corporations “on a leash”, it is worth following the process chronologically.

Regardless of whether a medium has a public or commercial function, Facebook and similar social networks offer different levels of opportunities to reach citizens, i.e. the target audience. One of the first and most important advantages of such mediatised networks is that they extend the scope and effectiveness of journalistic work since CMC, or more specifically new media, offer more opportunities than ever before to create direct contact between users, i.e. citizens and journalists. Second, Facebook and Twitter, which are already spreading the latest news at the speed of light, are deeply involved in the media consumption habits of ordinary people, while also encouraging users to spread current news of public interest through their own networks. Journalists – and the media companies behind them – therefore have a vested interest in being perceived as a trusted (news) source by users. In addition, it has also become common practice for media organisations worldwide to target their own content designed for social networks in an attempt to reach as many new users as possible (Moe 2013, 114).

By 2012, the world’s most prominent public service broadcasters, from the BBC in the UK to ARD and ZDF in Germany and ABC in Australia, have actively integrated social networks into their services. However, the commercial activity of the multinational – US-based – companies behind these platforms has been a major conundrum from the outset: public service broadcasters can be seen as national, and thus non-commercial entities, which, by using social networks, cross a hitherto clear boundary and enter the area of activity of global commercial enterprises (Moe 2013, 115).

2. Integration in two stages

The existence of public service broadcasting was justified by a specific political, technological and social context in the early 1920s, but the essence of public service broadcasting has changed over time. Despite an ever-changing media policy environment, broadcasters have sought to maintain their central role and to fulfil their public service mission. According to Karol Jakubowicz’s definition (2007, 115–116), “public service media can be identified with a service whereby media services are provided free of charge, as a ‘basic supply’ to individuals who require (such services) as members of a particular society and culture, an individual community and a democratic system, irrespective of the profit motive and the market supply.” By this definition, the services provided by state-operated public service institutions and public media services are linked at an essential point: public service media, like any other public institution, must provide basic supply to the citizens of a nation (Antal 2017). It is also important to emphasise here that the basis for the provision of services is not the individual but belonging to a particular community. Werner Rumphorst, in his explanation to the so-called Public Service Model Law (2007), captures this community aspect very concisely through his definition of a public service media service: a public service media service is a content service for society (the public), financed and supervised by it (Nyakas 2015, 143). The basic supply is based on the principle of universality, which means that all members of society should be provided with a diverse range of services (geographical coverage) – and consequently, with high professional standards.

From the very outset, public broadcasters in the Nordic countries have had a lot in common. Sweden, Denmark and Norway all established state-owned, national, publicly-funded, monopoly radio institutions in the period between the two world wars, and launched television in the same model in the 1950s and 1960s. Since then, both radio and television programmes have shared common features, based on a public service ethos, but are also similar in terms of form and content, as a result of cross-border cooperation. However, while public service broadcasting in much of Europe had entered a drastic decline by the early 2010s, it continued to enjoy the success it had enjoyed in the Nordic countries. It is therefore worth taking a closer look at the micro-processes that have taken place in the integration of global social networks, which operate on a commercial logic, in the case of NRK, one of the best-funded public service media institutions in Europe which is still popular with Norwegian citizens in the 2020s.

The Nordic public broadcasters’ approach to social networks should be divided into two phases: the first phase, starting in 2006, was characterised by random, ad hoc experimentation, but with high ambitions. The second phase, starting at the end of 2010, is more uniform and coherent than the first, but also shows a more moderate approach. And the transition between the two phases can best be captured along the lines of a shift from a bottom-up to a top-down approach. Below, this evolution is presented in greater detail on the basis of a study by Hallvard Moe (2013, 114–123), a media researcher at the University of Bergen.

2.1. Bottom-up integration between NRK and Facebook

The first experiments with web services by Scandinavian public broadcasters date back to the 1990s. This period was characterised by creative discovery, which in practice meant that enthusiastic media staff working for the channel started experimenting with the new world of networked communication on their own initiative. Meanwhile, as the web became a major media platform by the 2000s, public service broadcasters found themselves in a sort of regulatory vacuum as they sought to expand their web offerings – then with a small budget – to increase their reach to citizens. In northern European countries, the political sphere also gave public service broadcasters the green light to expand their responsibilities by exploiting the opportunities offered by the internet (Moe 2013, 117). As a result, public service institutions have set themselves the goal of becoming not only present on the web, but also part of it. In practice, this meant expanding beyond their own, existing main websites. In the case of NRK, this expansion also included the possibility of cooperation with other public sector organisations. By this time, global social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Myspace and YouTube were deeply integrated into the everyday lives of ordinary people. And Norwegian public service broadcasters have started to produce their own content for YouTube, even building studios for virtual worlds. One that stands out is Facebook, which was launched in 2004 at Harvard University in the US and has been available to the wider public since 2006. Facebook established itself as a dominant platform for computer-mediated communication in record time by the end of the 2000s. A search in the main Norwegian media database finds only seven mentions of Facebook in 2006, but already 1,154 in 2007. This number continued to rise in the following years, clearly indicating that Norwegian society was becoming more active in using the social network (SSB/MedieNorge 2010). In April 2007, NRK had its first success on Facebook. As part of a trial of an audiovisual service originally intended for mobile devices, the popular Norwegian comedian and sociologist Harald Eia created a fictional character called Rubenmann, a young male video blogger targeting a young audience. The character quickly gained popularity by deliberately posting amateur videos in which he posed dilemmas to his viewers (e.g. What would you do if you never cleaned your teeth again?).

As Rubenmann attracted mainly young viewers, NRK decided to take the experiment online. They started a separate blog for the fictional character, uploaded the video blog entries to YouTube and created a Facebook account for Rubenmann. Interestingly, it was the character who spoke on all platforms, not the comedian behind Rubenmann or NRK as an institution. The Facebook account in particular attracted the attention of users and the mainstream media, and this led to an expansion of the project over time – both in terms of scope and time frame (Moe 2013, 117). On Facebook, users could start a dialogue with the character and express their enthusiasm, send pictures, and so on. As Sundet (2008) argues, this project was a continuation of NRK’s practice of using new entertainment programmes or personalities to try new media services. On the other hand, Rubenmann was different in that there was no actual radio or television programme that it promoted or extended. Instead, the entire Rubenmann universe appeared without the familiar NRK logo, blurring the line between fiction and fact. Although the decision to move Rubenmann to Facebook was in line with the general idea of using external websites to reach new, mainly young, users, it was mostly perceived by the industry as an experiment with low expectations rather than a project based on a fixed and predefined strategy (Moe 2013, 118).

In the years that followed, Facebook and Twitter became increasingly part of the services provided by NRK. More and more radio and television programmes developed some form of presence on social networks, but overall, the Norwegian public service broadcaster’s approach to Facebook remained somewhat random and even disorganised. Anyway, in 2010 a survey showed that NRK’s news programmes had more than 30 accounts on Twitter and more than 20 on Facebook, and that did not include the individual accounts of journalists. However, these accounts varied considerably in terms of their connection to NRK. There was no uniformity in terms of naming, layout or the specific use of the services, but it was clear that the ambitions of the public service media provider were clearly growing in relation to the use of social networks (Moe 2013, 118). By the end of 2010, NRK’s main website, nrk.no, already included invitations to follow the channel’s Facebook and Twitter accounts. Moreover, the radio news programmes even featured the editorial team’s tweets on the nrk.no official page. At this point, social networking sites started to integrate more and more seamlessly with public service content. This integration was not limited exclusively to the web: television and radio presenters were also increasingly directing citizens to their Facebook or Twitter profiles, and the increasingly tight integration laid the foundations for a new phase in the relationship between NRK and social networks.

While NRK’s various editorial departments continued to experiment with Facebook and similar sites within their own competences, over time the world of politics and regulation began to catch up as a result of the regulatory developments in neighbouring Sweden – illustrating the transition to phase two.

2.2. Top-down integration of NRK and Facebook

The fundamental dilemma of the shift of public service information to social media was exemplified by a report by the Swedish public service broadcaster SVT in a morning news programme of a regional television on 21 May 2010 when reporting on the preparations for the wedding of Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden and Daniel Westing. There were still four weeks to go until the wedding and, according to the report, some clergymen in southern Sweden suggested that the Crown Princess should not be given away by her father, the King, as tradition dictates. After the report, the news presenter turned to the viewers and asked, “Should Victoria enter the church with Daniel or not? What do you think? Go to our Facebook page and tell us your opinion” (Moe 2013, 118–119). However, the programme was reported to the Swedish Media Authority for redirecting viewers to the Facebook page, which, after discussing the matter, concluded that the broadcaster, by mentioning Facebook and encouraging viewers to use a service, was “guilty of unjustified promotion of commercial interests” and violated the Radio and Television Act (Granskningsnämnden för radio och TV, 2010).

In this case, the Swedish public service broadcaster argued that Facebook was like a public space. Like in any public space, commercial actors can be present, but there are also important discussions about socially relevant issues, and therefore public service institutions should also be present there. However, the Swedish media authority did not accept the public space metaphor. It argued that a user agreement with a commercial company would have been necessary to take part in the debate on Facebook. According to this view, the public service broadcaster therefore published publicly funded media content “within the territory” of a multinational corporation controlled from the United States, or more precisely on its platform, which neither the Swedish broadcaster nor Swedish politicians could do much to regulate (Moe 2013, 119).

The intervention of an external regulatory body has thus revealed some fundamental problems with the public service broadcaster’s use of social media. In any case, the Swedish public service broadcaster has taken a new approach in the wake of the ruling – and so have public service broadcasters in neighbouring Nordic countries. Owing to this case, NRK began to develop internal guidelines for using social media (Moe 2013, 119). The guidelines, in force since the end of 2010, have set out some basic routines for reporting and documenting new initiatives, and also provided guidance on using services according to the “best practices”. The guidelines also included rules on how a broadcaster could refer to Facebook or Twitter from its own programmes or websites, stressing that social networks are commercial sites. It was argued that activities on Facebook or Twitter should support NRK’s services – and not the other way round.

The Danish public service broadcaster DR followed the Norwegian example in early 2011 and acknowledged the need to stop publishing exclusive content on social networks and to provide “strong editorial justification” for references to the named service. NRK’s document contained a similar rule. In March 2011, following a viewer’s complaint, the issue was referred to NRK’s Broadcasting Council, an external advisory body, which took the view that it was essential to be present on the platforms people use, but that the practice so far could not be considered perfect. The organisation stressed the need to continue to allow experimentation, while at the same time emphasising the importance of “branding NRK”.

By 2012, the Facebook link, the Twitter logo and the embedded Twitter news feed had also disappeared from the official NRK-affiliated pages of the above-mentioned radio and television news programmes. From then on, the use of social networking services at NRK entered its second phase, characterised by a much more modest approach than before, with less obvious connections, a more structured setup and a more uniform and concrete practice. By the end of 2012, revised internal guidelines were introduced, leaving much less room for individual, creative experimentation.

In this context, Moe (2013, 120) notes that there are also differences within the Nordic countries, such as the role of top-down regulation. While in Sweden the regulatory body intervened and directly brought about changes in how the public service broadcaster used Facebook, the shift to a more modest and more unified approach at NRK occurred without formal intervention by an external regulatory body. In a sense, NRK acted proactively, learning from the Swedish example, and solved the problem before the Broadcasting Council, the Norwegian Media Authority or any political actor paid any particular attention to the issue.

In any case, Moe (2013, 122) argues that all this shows that in a sense the power to provide information is shifting from national-political actors (with the exception of Norway) to global commercial actors, as the Swedish case also shows that by operating in the “territory” of multinational corporations like Facebook, the public service broadcaster risks acting outside the scope of the national regulator. However, this does not mean that it is an unregulated environment, as on Facebook, too, all users have to abide by the specific guidelines of the social network.

Summary

The Norwegian public service media model has served as a model in Europe for decades. However, the information revolution and the changes in social communication brought about by social networks have challenged the Norwegian government and the media authority, forcing them to create a new legal environment to adapt to the changed circumstances. But as can be seen from the above, the Norwegian competent authorities have focused on a single aspect in developing the new regulations: the preservation and creation of value by the public service mission.

As one of the best-funded public service media institutions in Europe, and still highly popular with Norwegian citizens in the 2020s, NRK’s integration of profit-oriented, commercially driven global social networks into its public service media system has not been a smooth process. In the initial phase, the use of media platforms such as Facebook appeared to have started from the bottom up, without institutional intervention, but over time, the authorities also sought to avert threats to citizens and the public service mission.

However, the – sometimes very significant – differences between European countries and broadcasters should not be overlooked when looking for the recipe for success of the Norwegian public service media model. In fact, the Norwegian public service broadcaster has been in a stable and strong position for decades, enjoying the respect and trust of the Norwegian society. It was therefore well positioned to integrate successfully into the innovative world of social networks.

References

- Antal Zsolt. 2011. Közszolgálati média Európában – az állami részvétel koncepciói a tájékoztatásban. (Public service media in Europe – The concepts of public participation in information.) Szeged: Gerhardus Kiadó.

- Antal Zsolt. 2017. „Közszolgálati kommunikáció, közbizalom és médiaszabályozás.” (Public service communication, public trust and media regulation.) In Medias Res 2017/2 319–338. https://szakcikkadatbazis.hu/doc/4459648

- Bayer Judit. 2008. A közszolgálati televíziózás újragondolása a digitális korszakban. (Rethinking public service television in the digital age.) Médiakutató 9/2 7–17. https://www.mediakutato.hu/cikk/2008_02_nyar/01_kozszolgalati_televiziozas_digitalis

- Bajomi-Lázár Péter. 2009. Hírközlés tegnap és ma. (Broadcasting yesterday and today.) Médiakutató 10/3: 141–147.

- Castells, Manuel. 2005. A hálózati társadalom kialakulása – Az információ kora, I. kötet. (The Rise of the Network Society – The Information Age, Volume I) Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1971. A társadalmi nyilvánosság szerkezetváltozása. (Structural change in the social public sphere.) Budapest: Gondolat Kiadó.

- Jakubowicz, Karol. 2007. Public Service Broadcasting: A Pawn on an Ideological Chessboard. In Media Between Culture and Commerce, editor: Els de Bens, Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Moe, Hallvard. 2013. „Public Service Broadcasting and Social Networking Sites: The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation on Facebook.” Media International Australia 146: 114–122. Viewed on 10 April 2022. https://journals.sagepub.com,

https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1314600115 - Nyakas Levente. 2015. A médiapluralizmus nyomában. A médiapluralizmus elvének elméleti alapjai és értelmezése az Európai Unió egyes politikáiban (különös tekintettel audiovizuális és -médiapolitikára), jogalkotásában és intézményi gyakorlatában. (In the wake of media pluralism. Theoretical foundations and interpretation of the principle of media pluralism in the European Union’s policies (with special regard to audiovisual and media policy), legislation and institutional practice.) Version prepared for discussion at the workplace. Doctoral thesis. Győr: Széchenyi István University

- Rumphorst, Werner. 2007. Model Public Service Broadcasting Law. Viewed on 10 April 2022. https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/model-psb-law.pdf

- Sundet, V. S. 2008. Innovajson og nyskaping i NRK. En analyse av plattform- og sjangerbruk i Rubenmann-prosjektet. Nors Medietidsskrift, 154/4, 282–307.

- SSB/MedieNorge. 2011. Tilgang til avisabonnement og antall abonnement.

- Tóth Loretta. 2022. Az udvariatlanság pragmatikája. Diplomácia 280 karakterben: a nemzetközi kapcsolatok alakulása a twiplomácia aranykorában. (The pragmatics of impoliteness. Diplomacy in 280 characters: the evolution of international relations in the golden age of twiplomacy.) Doctoral thesis. Budapest: Corvinus University.

1 Nordisk Film and TV Fond. Viewed on 3 April 2022. https://nordiskfilmogtvfond.com/news/stories/nrk-drama-impacted-by-norwegian-pubcasters-nok-300m-budget-cut-for-2023

2 Knut Kristian Hauger. 2022. NRK banker sparebudsjett: – Det har vært utfordrende. Viewed on 2 April 2022. https://kampanje.com/medier/2022/11/nrk-ledelsen-banker-budsjett-pa-sparebluss—det-har-vart-utfordrende/

3 Around 50 per cent of the cuts will affect content production, with the remainder affecting jobs, support functions and advisory services and investment. In practice, this means that some of the broadcaster’s productions will be suspended or postponed until 2024. However, it is important to note that news programmes are the least, whereas cultural and entertainment programmes the most affected by the restrictions. Nordisk Film and TV Fond. Viewed on 2 April 2022. https://nordiskfilmogtvfond.com/news/stories/nrk-drama-impacted-by-norwegian-pubcasters-nok-300m-budget-cut-for-2023

4 Medienorge.uib.no. 2022. Norwegian TV channels. Viewed on 3 December 2022. https://medienorge.uib.no/english/?cat=statistikk&page=tv&queryID=290

5 Medienorge.uib.no. 2022. Market shares Norwegian TV channels – result. Viewed on 3 December 22. https://www.statista.com/statistics/625792/audience-market-share-of-the-norwegian-tv-station-nrk1/

6 Reporters Without Borders. Norway. Viewed on 16 March 2022. https://rsf.org/en/country/norway

7 Internet World Stats. Viewed on 4 August 2022. https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats4.htm

8 Simon Kemp. 2022. Digital 2022: Norway. Viewed on 3 March 2022. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-norway

9 Share of population using the following media daily in Norway in 2022. Viewed on 10 May 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/572615/share-of-population-using-selected-media-in-norway/

10 General Data Protection Regulation. 2022. Viewed on 3 December 2022. https://www.datatilsynet.no/en/regulations-and-tools/regulations/

11 European Commission. Digital Services Act – Safety and accountability in the online environment. Viewed on 15 March 2022. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act-ensuring-safe-and-accountable-online-environment_hu

12 Government.no. 2000. The Norwegian Government Policy for Electronic Commerce. Viewed on 6 March 2022. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/The-Norwegian-Government-Policy-for-Electronic-Commerce/id419302/

13 Forbrukertilsynet.no. 2016. The Marketing Control Act. Viewed on 6 March 2022. https://www.forbrukertilsynet.no/english/the-marketing-control-act

14 Jeremy Gray. 2021. Norway passes law requiring influencers to label retouched photos on social media. Viewed on 15 March 2022. https://www.dpreview.com/news/1157704583/norway-passes-law-requiring-influencers-to-label-retouched-photos-on-social-media

15 Government.no. 2022. Hate speech and cyberhate. Viewed on 1 March 2022. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/equality-and-diversity/likestilling-og-inkludering/hate-speech-and-cyberhate/id2510986/

16 Tóth, Loretta. 2021. Nem várnak az EU-ra: három tagállam is nekimegy a techóriásoknak. (They won’t wait for the EU: three Member States fall on tech giants.) Viewed on 10 March 2022. https://magyarnemzet.hu/kulfold/2021/01/nem-varnak-az-eu-ra-harom-tagallam-is-nekimegy-a-techoriasoknak

17 Medietilsynet.no. 2021. Norwegian Safer Internet Centre: NSIC. Viewed on 23 February 2022.

https://www.medietilsynet.no/english/norwegian-safer-internet-centre-nsic/