Institutional framework, results to date

With regard to research in the field of Anthropology of the Theatre, we have reported on the work of our Research Group on Ritual, Theatre, and Literature at the Károli Gáspár Reformed University in our volume Poetic Rituality in Theatre and Literature (Domokos and Sepsi, 2021), as well as in several individual publications (monographs and studies.1 The publication of the encyclopaedic, theoretical and at the same time practical handbook on the Anthropology of the Theatre by Eugenio Barba and Nicola Savarese (A Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology: The Secret Art of the Performer) in the Károli Books series also represents an important milestone in this field. This publication was accompanied by personal meetings and public discussions. The results of the research were also incorporated into the theatre science training at Károli in the course of model curriculum reforms, through which we repaid several decades’ worth of debt. The reason for our mentioning results garnered from the Anthropology of the Theatre in an article concerned with the Sociology of the Theatre is that we agree with the assertion of Patrice Pavis that Sociology is almost slipping into the uncharted domain of Anthropology, which may be due to the fact that researchers appear to be opting for a more universal, less social perspective rather than specific, local findings.

Perhaps also for the same reason, fewer results in the field of the Sociology of the Theatre have been achieved to date in Hungary. Of these, the most important theoretical results are undoubtedly found in the volume edited by Katalin Demcsák, Zoltán Imre and Péter P. Müller entitled At the Border of Theatre and Sociology (Demcsák et al., 2005), which includes Hungarian translations of studies by Maria Shevtsova and Claudio Meldolesi on disciplinary boundaries and interdisciplinary interactions, and Zoltán Imre’s article on audience research, as well as a foreword by Katalin Demcsák. Maria Shevstova, who was influenced by Pierre Bourdieu, has developed a questionnaire for the Anglo-Italian audience in Australia, in which she outlined the socio-cultural profile of the audience and which can be used, with various modifications, for student theses. This treats the following aspects:

1. The social composition of the audience

(gender, age, ethnic group, education, occupation)

2. The viewer’s relationship with Italy

(for bilingual English–Italian performances)

3. Knowledge of and relationship with Italo-Australian information sources

4. Cultural standards and knowledge of the arts

5. Other visited theatres

6. How two pieces interact and change

7. Suggested themes for the company’s or group’s next mise en scène

8. What audience is the company targeting?

Audience surveys, primarily but not exclusively commissioned by theatres, are being conducted more frequently across Europe, yet few large-sample questionnaire surveys have been conducted in the field of reception research, and the results of these small surveys with samples of up to fifty people are not always readily available. The newly established Károli University Research Group on Theatre Education and the Sociology of Theatre will write a summary of the methodology of this type of research and conduct questionnaire-based and focus group surveys with the participation of students working on their theses.2

Studies on reception are complex, since they usually involve the representatives of not one or two, but several disciplines. Our recent study with NoldusFacereader8 on artistic experience (in terms of the six basic emotions) was published in two papers (Sepsi 2019, and Sepsi, Kasek and Lázár 2022).

The questionnaire that was developed by the earlier international STEP research did not focus on social (for example, demographic) data series, but on mapping the experiences of the audience.3 That is why we will be able to use it as a methodological compass for the work of students and researchers. We will present a number of these previous, hard-to-access research results (Szabó 2019) in the following sections of this study.

Outlines of an international comparative research study on reception

Between 2010 and 2013, the research of the STEP Theatre Sociology Research Group ‘City Project’ attempted to map theatre systems in several European countries and examine in detail the audience experience and the links between the said systems and the experiences. Some members of the research team have evaluated the results of the audience research in several individual and co-written papers, and are currently preparing an English-language volume, which will primarily present the methodological conclusions of the research. The STEP theatre sociology research group was established in 2005 with the aim of examining the theatre systems of several European countries by way of international comparison and exploring the various aspects of the role of theatre in society. Researchers from the Netherlands (the University of Groningen), Ireland (Trinity College Dublin), Denmark (Aarhus University), Slovenia (AGFRT Ljubljana), Switzer¬land (the University of Bern), Estonia (the University of Tartu) and Hungary (the University of Debrecen, OSZMI) have participated in this collaborative initiative. The first tangible result of the research team was the volume Global Changes – Local Stages, which was published in 2009, and which presents, through individual studies, the following specific characteristics of the theatre systems in the seven countries: the impact of social changes on theatre systems, the value system of theatre policy, the different practices of theatre funding, the reception of the values of theatregoing, and the relationship between systems and aesthetics (Van Maanen et al., 2009). The reception research of the City Project was presented in a special bilingual issue of the Slovenian journal Amfiteater (Šorli 2015). The research team’s most recent academic publication is The Problem of Theatrical Autonomy (Edelman et al., 2016), but a number of papers and conference presentations have been produced as a result of their joint work.

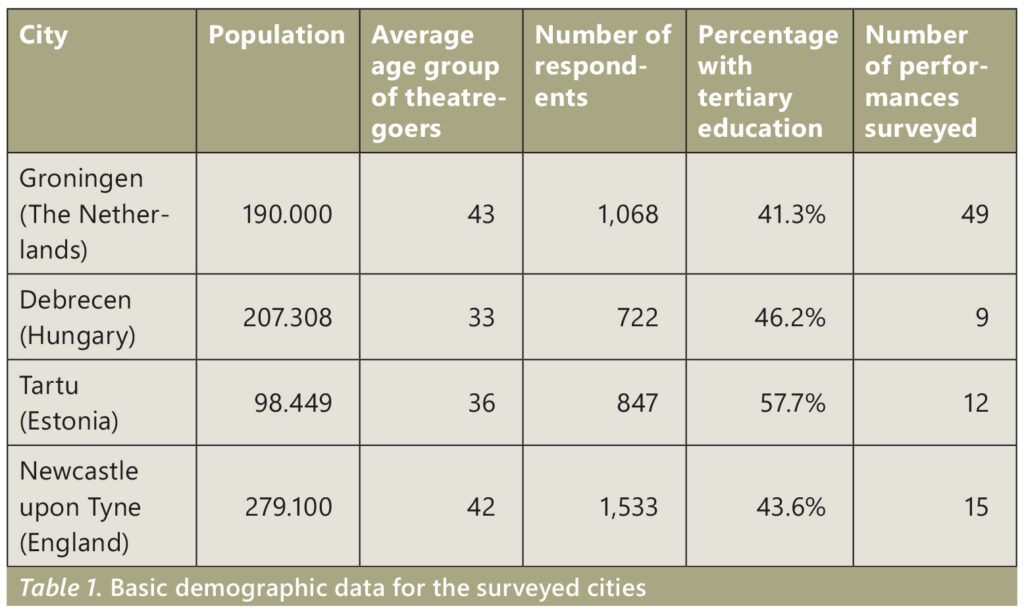

In the STEP City Project research initiative, the aim of the work was to produce in-depth comparative studies on the functioning of the theatre systems in the participating countries, following a thorough collection of material with the same methodological background. The following cities participated in the descriptive part of the research: Aarhus (Denmark), Bern (Switzerland), Debrecen (Hungary), Groningen (the Netherlands), Maribor (Slovenia) and Tartu (Estonia). In addition to a comprehensive mapping of the theatrical and cultural offer in each city, audience surveys conducted by way of questionnaires were also possible in four of the cities.4 The possibility of comparability was an important aspect in the selection of the cities: the research group chose medium-sized university cities operating as regional centres, which, with the exception of Bern, are not capital cities. With respect to a local tender, we were also able to conduct a survey in Newcastle and the Tyne region in the North of England. The City Project data collectors used the same detailed questionnaire in each city, which, in addition to the motivations for going to the theatre, aspects of choice of play, frequency of theatre attendance and general demographic data, was primarily intended to explore the audience experience of the performance. Respondents were asked to rate most questions on a six-point scale, with 6 indicating total agreement and 1 representing total disagreement. The theoretical principles of the research are summarised in detail in Hans van Maanen’s study on the Sociology of Art, which was published in 2009. The methodological and practical issues of audience research were developed jointly by the STEP research group, under the guidance of Sociology of Art researchers at the University of Groningen5.

When describing the theatre systems, not entirely unexpectedly, the research team was faced with significant differences between the Eastern and Western European systems. The theatrical offer of university centres of a similar size is significantly larger in England and the Netherlands, which is undoubtedly linked to the intrinsic way in which the systems operate: the touring system in the Netherlands and the predominance of en-suite theatre in England account for the greater variety, while in Hungary and Estonia the permanent company form of repertory theatre dominates the theatre offer in the cities studied. However, the disadvantage of touring systems is that a performance can only be seen two or three times in a given city, so it reaches fewer viewers overall. However, audiences in Eastern European cities are considerably younger and theatre plays a more important role in the education system than it does in Western cities. Season ticket schemes offered to schoolchildren and university students are only common practice in eastern cities. Dutch and English theatre, on the other hand, is significantly more effective in reaching the retired age group.

Important differences were also found regarding motivation for going to the theatre:6 the peculiarity of Newcastle was that music seemed to be the most important factor, although musical works did not dominate the sample. There were also differences in audience expectations of theatre: in Western European countries the need for entertainment is stronger, while in Eastern Europe theatre represents an important arena for learning, cultural education, and self-improvement. Western audiences generally found theatrical impressions considerably more entertaining, and this was not only the case in the lighter genres such as cabaret and musicals, but also in the appreciation of prose theatre (van den Hoogen 2015, 357)

That said, the important conclusion drawn by the City Project survey as a whole was that the differences between East and West in terms of viewer experience appeared to be relatively insignificant. The majority of respondents were for the most part satisfied with the quality of the productions, regardless of the city in whose theatre they saw it. The highest average score for all questions was given by the English respondents, who rated the presentations they had watched with an average score of 5.54, very close to the six-point maximum. However, respondents in Tartu, Debrecen and Groningen also gave a 5-point rating, indicating high satisfaction. On average, the highest scores in the four cities were awarded for the performance, the evening as a whole and the acting. This was followed by an assessment of the building, the theatrical forms, the staging, the appeal and recognisability of the theme, the attributes of the characters and the story. The lowest ratings were given to the negative indicators, overall, with respondents feeling that the performance was overly unconventional, complicated, burdensome, superficial, or boring. Personal relevance also scored below average, and respondents did not find the productions either comforting or challenging.7

The personal and social relevance of theatre in the light of audience opinion

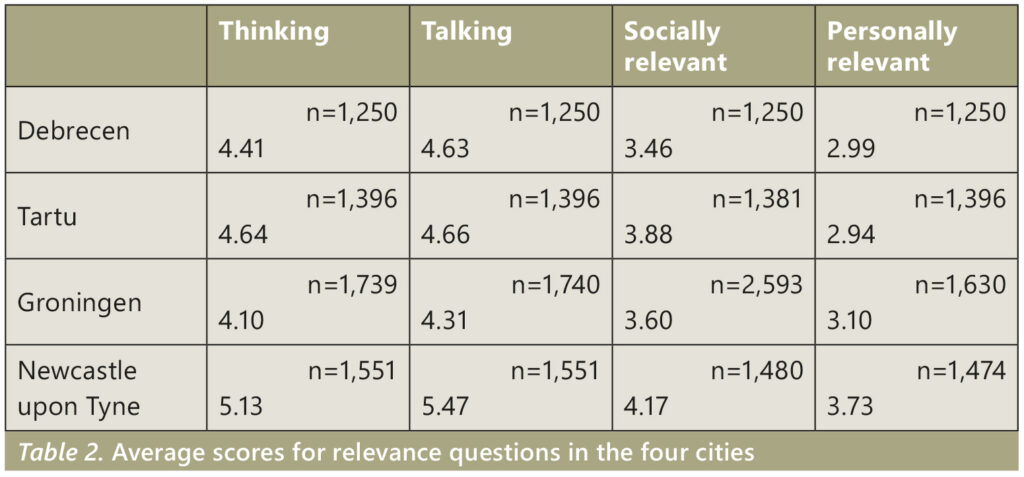

The Sociology of Theatre mainly focuses on the reception of theatre by the community, and its patterns, which the STEP research group attempts to discover in the realisation of artistic values, and in the operation of the social functions of theatre. The questionnaire research revealed surprising correlations between the respondents’ personal and social evaluation of theatre. The study asked how much the respondents considered the given performance to be personally and socially relevant. In addition, in the following section of the form, they were also asked how much they considered what they saw in the theatre to be worthy of thought and discussion. Somewhat surprisingly, personal involvement was rated below average in all the cities, where, in addition, talking about presentations was rated slightly higher than thinking. The social relevance of the presentations was rated around average in the case of Tartu, and below average in the three other cities. The perception of personal attachment scored even lower. One interpretation could be that, on average, the respondents felt less that the productions in the survey were directly for or about them. When asked if the actors expected anything from the audience, the responses were higher than for personal involvement (Debrecen 3.468, Tartu 4.17, Groningen 3.24, Newcastle 4.17).

Correlation coefficients can further refine the relationship between relevance and processing in a company. The data shows that audiences in all four cities like to think as well as talk about the performance in question. The correlation between the two questions is very strong, averaging 0.75. The higher they rated a performance, the more willing they were to share their opinion with others, and this was particularly true in Groningen and Newcastle. However, whether the performance was socially relevant was less important in evaluating the evening as a whole. We found above-average willingness to share theatregoing experiences in all four cities. The English, Hungarian and Estonian respondents, and finally the Dutch, enjoyed talking about the performances with others the most. In all cities, social processing was preferred to thinking about the performance, but Newcastle showed the greatest difference in this respect.

Thus, the questionnaires reveal that audiences mostly see the same performances as socially and personally relevant, yet they see theatres as failing to make them feel more personally involved in exploring socially relevant issues, or they refrain from acknowledging personal involvement. This is confirmed by the correlation between personal involvement and thinking, which is also low, especially in Debrecen and Newcastle. Since more emphasis is placed on speaking rather than thinking, and social relevance instead of personal relevance, it can be hypothesised that the audiences in the four cities value theatregoing as a social event rather than an opportunity for personal development.

However, it would be premature to conclude that theatre is no more than a social gathering. The evaluation of the performance as a whole, the experience of the evening spent in the theatre and the evaluation of the theatre building paint a different picture. Examining the entire sample, in all four cities the closest correlation was visible between the evaluations of the performance and the evening. We observed a weaker but still very significant co-movement between the evaluation of the evening as a whole and the theatre building. Finally, the rating of productions showed the weakest correlation with the buildings. This result, which was measured on a relatively large sample, confirmed internationally the common idea that the primary role in the perception of theatre as a social practice is played by the theatre production and its quality.

How important do viewers believe that it is for good performances to be socially relevant? Examining the prose productions, social relevance was rated only tenth in terms of the strength of the correlation. The respondents primarily valued the effectiveness, professional sophistication, interesting, exciting, inspiring nature and completeness of the theatre experience. Social relevance showed a relatively significant co-movement with the respondents’ perception of the performance in Groningen (correlation coefficient .436), while in Tartu and Debrecen this correlation was slightly lower (.323, .313), and in Newcastle the weakest (.140). According to another question, the respondents regarded the captivating setting of the story, the quality of the direction and the performance as most important. Overall, we can see that the most important factor for audiences to judge a good performance is its captivating nature.

Although the autonomous, aesthetic aspects proved to be important, it cannot be said that the degree of relevance of the presentation is not also significant. The theme of the work scored highly on the list of criteria for the selection of a theatre performance in all four cities: in order of importance, it was ranked second in Groningen and Newcastle, third in Debrecen and fifth in Tartu. In Debrecen, the importance of the subject matter decreased with the educational level of the respondents, ranking third among those with a certificate of secondary education, fourth among those with a BA degree and fifth most important among those with a PhD. The same correlation was also found in Tartu, but in Groningen and Newcastle the topic matter was of equal importance, regardless of education. This result supports the hypothesis that more highly educated and experienced theatregoers are more willing to view theatre performance as an autonomous art form, a complex work of art, rather than an arbitrary medium for telling a story. The results of the STEP audience research may provide additional opportunities for a deeper analysis of this connection, which cannot be discussed in detail here.

The questionnaire survey that was conducted in 2012 concerned nine performances in Debrecen9. In terms of both social and personal relevance, the Debrecen audience considered the staging of Igor Viripayev’s contemporary play, Illusions, to be the most outstanding performance of the time. Viktor Ryzakov’s direction was also highly rated in terms of form, but in comparison with the other performances it did not receive as much acclaim as the high rating awarded for social and personal relevance. Second place was awarded to the Csokonai Theatre’s production of Peter and Jerry, surpassing Illusions in terms of social relevance, but falling short in terms of personal relevance. The prominent position of the Hajdú Táncegyüttes folk dance performance in the ranking is surprising, probably reflecting the views of respondents who are folk dance enthusiasts. The twenty-two respondents aged 18-38 attended amateur or folk dance performances more often than the others, with an average of 1.7 times per year, compared to 1.3 for the full sample. Although the reception of the performance was neither challenging (2.9) nor difficult (2.46), it was extremely interesting (5.73), mainly due to the high technical ability of the dancers (5.5). Respondents considered the dance performance to be both socially (3.9) and personally (4.1) relevant, and this was reflected not only in the scores but also in the free text responses. Public opinion showed that it was definitely worth talking (5.0) and thinking (5.47) about the performance. The positive reception of the folk dance performance suggested that not only plot-driven prose genres but also dance performances of high artistic quality have the potential to engage the audience in their own world (5.54) and activate their imagination (5.47).

The Tragedy of Man, which was directed by Attila Vidnyánszky, ranks fourth in terms of relevance, and has received outstanding ratings based on the viewing experience, which is mainly due to the excitement it generated. In terms of theatrical form, the stand-up comedy night in Lovarda scored higher than The Tragedy of Man in terms of both social and personal relevance, but offered a considerably lighter experience in terms of the viewing experience. The university theatre company SzínLáz performed its own adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in non-theatrical, so-called “found venues”, namely, the university basement and the Botanical Garden, which the audience, for the most part university students, found outstanding for its personal connectivity. They praised the humour of the performance and the intriguing treatment of the themes raised.10 Scoring lowest in regard to relevance were a Puccini opera, a puppet show and the Körúti Színház’s adaptation of Meseautó, which was a guest appearance in the city. What these three presentations have in common is that their aesthetic dimension scores are higher than their relevance factor scores. The puppet performance received the second highest score for formal execution (5.35), but it remained below average in terms of relevance. Meseautó, a guest performance at the Railway Workers’ Cultural Centre, scored the lowest in both social and personal relevance, although it is fair to say that this is not the fundamental purpose of this particular form of entertainment. Its reception is not particularly demanding for the spectator (2.22) and, with the exception of the entertainment aspect, it scores below average for theatrical forms. Many respondents expected a staged version of the well-known film and wanted to hear the popular songs live, recalling the humorous moments and turns of phrase uttered by the star actors in the classic film in the stage production. The title track was one of the songs that was missed by the audience from the music, which was rearranged to create a more modern sound. The majority of the free text comments were highly critical of the theatre hall: parking difficulties, ventilation, the technical state of the stage, and the sound system all came under criticism. In this case, it is clear that, despite the overall satisfactory performance (5.16), the inadequacy of the theatre building (3.96) was a factor that reduced the overall rating for the evening (4.78).

The high relevance scores of the performance of Illusions in Debrecen show that a contemporary drama that is performed with a strong theatrical vision can be extremely relevant, even if it deals with personal rather than social issues. The two actresses, Magdolna Vass and Nelli Szűcs, and the two actors, Zsolt Trill and Attila Kristán, speak “directly” to the audience with the help of microphones, in a monologue-based dramatic structure that is very typical of Viripayev’s plays. Audiences were most impressed by the acting (5.46) and the theme (5.23). Several respondents highlighted the non-instrumental presence of the actors, the direct, authentic performance and the natural style of the acting. Both the direction (5.0) and the theatrical forms presented in the performance (4.8) received high scores, and the mise en scène was considered to be in no way too conventional (2.2). Several respondents mentioned the baking of a cake on the stage as their favourite scene, in which the actors shared the cake with the audience at the end. This further strengthened the immediacy of the play, and the common celebration dissolved the boundaries between actor and the viewer, and viewer and other viewers. The sense of relevance of the performance was also strengthened by the decision made on the form of the play: at a certain point the respondents could see video interludes in which residents of Debrecen talked about love. This is not only a formal innovation in the palette of instruments of the Csokonai Theatre, but also, as one of the viewers explained, “film clips of the man in the street made the problem raised very real”.11 Another respondent also praised Ryzakov’s courageous directorial choices, which represented a deviation from the usual norm. The close connection between theatrical form and relevance was eloquently expressed by a 43-year-old woman who liked the final scene of the performance best, “when the actress offered the audience the cake she had made. This made the performance, which had been ‘scratching’ human emotions, very human. Making the cake during the presentation was an extremely innovative and logistically challenging exercise anyway.”12 It is noteworthy that, although the characters and actors are between thirty-five and forty years old, the secondary school audience also considered the performance relevant to them, significantly more so than those over thirty-five. The performance is thought-provoking (5.1), worth discussing (5.06), not challenging to watch as a theatrical experience (3.04), as it is light (4.0), easy to follow (4.0) and entertaining as a whole (4.6). Thus, although Illusions is essentially a staging of a contemporary drama on a personal theme using the tools of the director’s theatre, at several points the mise-en-scène uses more the tools common in documentary approaches for “breaking down” the fourth wall.

Besides Debrecen, it is also true for the other cities that the audience did not consider the productions of classical dramas to be the most relevant, but rather contemporary texts. These works generally received average ratings for social relevance in all the cities: in Debrecen, The Tragedy of Man (3.75), in Groningen, Mesél a bécsi erdő (Tales from the Vienna Woods) (3.48), in Tartu, Oblomov (4.18 – where the average is 4.19), and in Newcastle, Pygmalion (4.32 – where the average is 4.62). The specificity of Newcastle is that while the indicators for the aesthetic and general evaluation of the evening are the highest, the respondents’ evaluation of personal relevance is the lowest. The classical operas La bohème, Carmen, and Tosca, did not stand out for their topical content, either. Musical entertainment performances and musicals also scored similar or even lower ratings.

Further lines of research

The STEP quantitative research study, an internationally unique undertaking, sought to map the detailed experience of viewers in distant cities, using the same questionnaire, in a large sample, in a theoretically reflective framework. The large amount of empirical data collected provides many as yet untapped research opportunities, which, beyond their local relevance, may reveal remarkable theoretical connections in systems of European theatre-viewing experience. It is also true, meanwhile, that in the process of interpretation, researchers face several obstacles with regard to methodology and data collection, which make the given reading difficult or even impossible. Audience research has shown that European audiences value the relevance of theatre performances, considering it a separate aspect from other artistic functions of the performance (for example, entertainment). Just because a performance is entertaining does not mean that it cannot also be very relevant at the same time, but the most important thing for the theatrical experience is the quality of the artistic presentation, the overwhelming nature of the performance, and its worldliness. Personal relevance was ranked unexpectedly low in all the European cities examined, which leads us to think further about the complex cognitive mechanisms of viewer identification. At the level of reception, there are differences between “western”, mainly privately operating theatre systems (for example, in England) and “eastern”, state and municipally owned theatre systems (for example, in Estonia), but both structures are capable of producing performances that address significant social issues and that are perceived and appreciated by audiences in all four cities in a similar way. In each city, contemporary texts, transcripts or staging embedded in a specific topical context proved to be more relevant for the viewers than classical dramatic representations. From the methodological point of view, it was revealing that the analysis of a performance with regard to reception can be greatly enhanced if a significant number of well-documented audience opinions are available in a quantifiable form, which we were only able to glimpse briefly in this study. The STEP research team is currently working on a large amount of empirical data. An upcoming multi-authored volume will mainly present the methodological aspects and lessons learned from the research, and is expected to be published in 2023 in the Routledge theatre audience research book series.

A starting point for further investigation of the relationship between personal identification (empathy) and relevance is the application of our earlier study on the reception of artistic experience (Sepsi 2019 and Sepsi, Kasek and Lázár 2022), which would entail the addition of a larger sample size psychometric analysis to the methodology. In this study, the micro-facial expressions recorded by Noldus were assessed in the light of psychometric tests to obtain a more nuanced picture. Given the importance of early mother-child and father-child experience in the development of empathy skills, and their involvement in the development of mentalisation and mirror neurones, we scored the mimic reflection of the reception of artistic experience according to the poles of the empathy, attachment, and parenting scales. When examining the overall test sample for empathy and microexpressions measured with the Noldus Face Reader 8 tool, we observed that the mimic responses among the subjects with low overall empathy that were revealed in the microexpressions found by the programme clearly show a predominance of angry, sad, surprised or disgusted responses, while for subjects with higher than average scores, cheerful expressions predominate over surprised and occasional angry or sad expressions. The psychometric tests made it possible to examine this indicator of artistic reception in the context of developmental psychology. Similarly, the STEP methodology can be supplemented with a psychometric questionnaire survey with a larger sample.

Further research employing a similar methodology is currently being conducted at the Institute of Fine Arts and Liberal Arts of the Károli Gáspár Reformed University, and an adapted version of the questionnaire presented here is currently being used by an MA student of Theatre Studies in his thesis, analysing the reception of a performance staged by the National Theatre, mainly from the perspective of secondary school students. This autumn, another student will begin research on a similar optic. We will provide an account of these results later within the framework of co-authored and individual studies, in addition to which we also plan to write a seminar notebook that will introduce the students to the methodology of the Sociology of Theatre, thereby encouraging the birth of further academic student works.

References

• Demcsák Katalin, Imre Zoltán and P. Müller Péter. 2005. Színház és szociológia határán. Budapest: Kijárat Kiadó.

• Domokos Johanna and Sepsi Enikő, ed. 2021. Poetic Rituality in Theater and Literature. Budapest: KRE–L’Harmattan Könyvkiadó – Károli Könyvek.

• Edelman, Joshua, Louise Ejgod Hansen, Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen. 2016. The Problem of Theatrical Autonomy: Analysing Theatre as a Social Practice. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048530274

• Edelman, Joshua and Šorli, Maja. 2015. “Measuring the value of theatre for Tyneside audiences.” In Cultural Trends 24:3, 232–244.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2015.1066074

• Edelman, Joshua, Maja Šorli and Mark Robinson. 2014. The Value of Theatre and Dance for Tyneside’s Audiences. Arts and Humanities Research Council – Cultural Value Project. Viewed on 1 May 2022. https://www.thinkingpractice.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Value-for-Tyneside-Audiences.pdf.

• Šorli, Maja, ed. 2015. Amfiteater 3 (1-2), AGFRT Ljubljana, 235–273. Viewed on 03.06.2022. https://issuu.com/ul_agrft/docs/amfiteater__web_3pika1-2

• van den Hoogen, Quirijn Lennert and Anneli Saro. 2015. “How theatre systems shape outcomes.” Amfiteater 3 (1-2), AGFRT Ljubljana, 357–363.

• van Maanen, Hans. 2009. How to Study Art Words On the Societal Functioning of Aesthetic Values, 150–202. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

https://doi.org/10.5117/9789089641526

• van Maanen, Hans, Andreas Kotte and Anneli Saro, ed. 2009. Global Changes – Local Stages. How Theatre Functions in Smaller European Countries. Amsterdam: Rodopi. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789042026131

• Pavis, Patrice. 2003. Előadáselemzés, Translated by Jákfalvi Magdolna. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó.

• Sepsi Enikő, Kasek Roland and Lázár Imre. 2022. Művészeti befogadás pszichofiziológiai vizsgálata Noldus Facereader segítségével. In: Érzelmek élettana járvány idején, ed. Lázár Imre, 212–227. Budapest: KRE–L’Harmattan Könyvkiadó – Károli Könyvek.

• Sepsi Enikő. 2019. A művészetbefogadás pszichofiziológiai vizsgálatának lehetőségei (irodalom, színház, film). In A társas-lelki és művészeti folyamatok pszichofiziológiája, ed. Lázár Imre, 293–299. Budapest: KRE–L’Harmattan Könyvkiadó – Károli Könyvek.

• Szabó Attila. 2019. A kortárs színház társadalmi és személyes relevanciája egy nemzetközi színház-szociológiai kutatás eredményei alapján. In: Színház és néző, ed. Burkus Boglárka and Tinkó Máté, 152–176. Budapest: Doktoranduszok Országos Szövetsége, Irodalomtudományi Osztály.

• Vásárhelyi Mária. 2005. „A színház egy zárt világ?” In Színházi jelenlét – színházi jövőkép, ed. Szabó István, 139–151. NKA Kutatások 1. Budapest: Országos Színháztörténeti Múzeum és Intézet.

________________________________________

1 See the website of the research group: http://www.kre.hu/portal/index.php/ritus-szinhaz-es-irodalom-cimu-kutatasi-projekt.html

2 Besides its research on reception, the work of the research group also extends to the field of theatre education, which is led by Ádám Bethlenfalvy, who formulated the directions of research as follows: in 2013, a research study, which was unique on an international scale, was conducted in Hungary, mapping the situation of theatre education in Hungary, and, on the basis of its findings, provided terminology and an overview for both those working in the field and for scholars of culture and education. In 2023, a decade after the original study, it would be necessary to take another snapshot of the domestic situation, and to document it once more, and on the basis of this, to formulate recommendations, insights and directions for decision-makers, researchers and those working in the field. Theatre education has become important in the operation of independent theatres, and nowadays many permanent theatres successfully run such sections and groups. In the meantime, a number of professional (artistic and educational) good practices have been implemented in accordance with artistic and educational paradigms, which demonstrates that theatre education can be integrated into the operation of various types of theatre institutions. This research could significantly contribute to the awareness and development of theatre education in the professional medium of permanent theatres.

Contributing researchers from the faculty of Károli University: Ádám Bethlenfalvy, Enikő Sepsi, Attila Szabó, Gabriella Kiss, István Lannert, Gábor Körömi. Prominent researchers of the second generation of theatre education, graduates of the KRE Master of Theatre Studies: Anikó Fekete, Krisztina Bakonyvári, Eszter Vági, Edit Romankovics, Melinda Gemza. National and international experts participating in the research team: Ádám Cziboly (Western Norway University), Dániel Golden (SzFE).

3 Summary studies of previous research are available here (Amfiteater, Ljubljana): https://slogi.si/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Amfiteater-_web.pdf.

4 The English version of the questionnaire can be found in the study The Value of Theatre and Dance for Tyneside’s Audiences, but the Hungarian version has not yet been published.

5 Due to the unique working method of the research team and the enormous resources required for the extensive empirical research, all publications related to the results of the City Project can only be understood as collective intellectual creations. Although the formal conventions of scientific publication render it less possible to intellectually honour this kind of joint creative work, at least in the form of a list, I would like to mention the names of the participants in the research: Magdolna Balkányi, Zsigmond Lakó, Zsófia Lelkes (Debrecen), Louise Ejgod Hansen (Aarhus), Andreas Kotte, Frank Gerber, Beate Schappach, Mathias P. Bremgartner, Frank Gerber (Bern), Hans van Maanen, Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen, Marine Lisette Wilders, Antine Ziljstra, Anne-Lotte Heijink (Groningen), Ksenija Repina Kramberger, Maja Šorli (Maribor-Ljubjlana), Anneli Saro, Hedi-Liis Toome (Tartu), Joshua Edelman, Stephen Elliot Wilmer, and Natalie Querol (United Kingdom, Ireland).

6 The STEP research group survey on the motivation for theatregoing essentially confirmed the findings of Vásárhelyi’s 2005 survey in Hungary (Vásárhelyi 2005).

7 The research group believes that the exceptionally high values in England, which are indicated in almost every group of questions, can be explained by the fundamental differences between the theatre systems. In the English theatre structure and in the selected sample, the presence of private theatres is considerably more significant, and the state support of theatres is not as extensive as in other countries. According to the STEP group’s hypothesis, therefore, the majority of viewers are not so critical of theatres that do not operate with public funds.

8 Those filling the questionnaire were asked to express their agreement with the given question on a 6-point scale, where 6 indicated the highest and 1 the lowest agreement. In the following, the numbers in parentheses represent the average of the opinions of the respondents.

9 The questionnaire survey was conducted by Dr. Magdolna Balkányi, Associate Professor of the Institute of German Studies at the University of Debrecen, with the participation of Zsigmond Lakó, Assistant Professor and students of the Department of Theatre Studies of the University of Debrecen.

10 It is also important to point out that only forty-four questionnaires were returned, while only forty viewers were able to attend the performance at any one time.

11 Excerpt from the free text answers of the questionnaire used in Debrecen, recorded by the research team after the performance of Illusions at the Csokonai Theatre. Question 13: Which part of the performance did you like the most and why? The questionnaire was completed anonymously.

12 Ibid.