Photo: Johanna Weber

For decades, you have been a prominent artist on the world theatre scene, a pioneering innovator of contemporary theatre language, both in practice and in theory. Your work ranges from Brecht to research and reinterpretation of the ancient Greek theatre tradition. It is a fascinating question as to which cultural strata this diverse and rich oeuvre is drawn from. I understand that, among your Greek origins and many other inspirations, you have also been influenced by Georgian culture.

■ Yes, my parents lived in Georgia for a while and only went to Greece in the early 1920s. But their families originally fled to Georgia from Trebizond (now Trabzon – A. K.) on the Black Sea coast of Turkey. As a child, my mother was sent to a village called Takova and my father to Sukhumi in Abkhazia. Then, around 1921 or ’22, they had to flee again, so they moved to Greece as children; my mother was only four years old, my father ten. They only met much later, in Greece, and had four sons, of whom I am the youngest. My eldest brother, who is now eighty-five years old, taught International Law at the University of Leipzig for many years.

The experience of constant change and encounter with different cultures was an important part of your family life. How did this affect you as a child and how did it influence your later life and thinking?

■ In our family, several languages were spoken at home. I heard them speak Russian and Turkish, for example, as well as a dialect of Greek used in Pontus1. Indeed, I could say I grew up in a multicultural environment, but they were all close, almost sister cultures. I heard one of my grandmothers singing Turkish laments and the other one was singing Russian laments. They were singing these songs in an ancient, archaic way; I remember them sitting on the floor with their hands on their hips, almost looking like some kind of Bacchae. They sang about their lost homeland, their connection with nature, and of course about their faith, their Orthodox religion. These songs had a very intense tone and were accompanied by dances. For example, they were well acquainted with the ancient Greek fire dance, and I saw them dance it passionately on several occasions. It was as if these people coming from the Caucasus were evoking the radiance of the culture of ancient Athens.

Can it be said that your theatrical thinking and mentality is rooted in these childhood experiences, among other things?

■ Of course, I was very much influenced by the fact that I realised my Middle Eastern roots at a very early age, as a child. It was an important realisation for me, and it has accompanied me throughout my life. When my parents came to Greece, they brought with them a clear-cut, diverse culture, which was reflected in their everyday life, in their songs, food and eating habits, in the way they brought up their children. My paternal grandmother, whose name was Despina, graduated from an almost university-level secondary school in Trebizond2, and knew ancient Greek. I grew up hearing the terms and concepts of the ancient Greek language from her. Previously, their family was in a privileged position, and represented a wealthy, cultured class. My grandfather, for example, wrote some great travelogues, including a wonderful text about the Caucasus. From this point of view, the impulses I had as a child represented a high-quality cultural experience for me. And despite the fact that we lived in a small village in Pieria, at the age of eight I was reading Dostoevsky and discovering several masterpieces of world literature, and by the age of seventeen I could speak Italian and read Dante in the original. So my family background was a very strong motivation for me, and that’s where my love of reading and writing came from. Of course, typically of refugee families, they always had to leave everything behind when they fled and moved, so they were constantly losing everything they had. My parents were farmers, typically left-wing in their thinking. Although my grandparents could still be called well-off capitalists, by the time they got to Greece they had lost everything and become communists. Both my father and my grandfather were active members of the Greek Communist Party, which, of course, [meant that] they later suffered. My mother’s family were also refugees, we lived in great poverty, and I was often told to leave the village because they could not give me what I needed there, only poverty. I left at the age of twelve, and went to high school in Katerini, but in the meantime I worked in a small grocery store, delivering groceries to customers’ homes, or helping the waiters, even washing dishes. This was the only way I could support myself. But, of course, whenever I could, I was always reading world literature, Russian, French, German writers… I have to add that my father was not an Orthodox Christian, but belonged to the Protestant denomination, so I had the opportunity to visit the library of the Protestant church and I started learning Italian, German and English at a very young age. Leaving the family home at such an early age helped me face reality and stand on my own two feet, but I never really had the joy of a happy childhood. In the summers I went back to our village and worked in the fields with my siblings. From the age of five, my parents took me to the fields where our family grew tobacco at that time. I remember being taken out at dawn in a basket, in which I slept, and they were picking tobacco from sunrise.

So for me, the refugee family background has always been a memory of a lost homeland, a lost culture, along with poverty and a lot of reading. All my siblings loved to read, and we inherited the love of reading from our mother. And also the sense of freedom, the knowledge that we can turn the world around even if we are alone, and that opened a lot of doors to me. In other words, I matured very early and felt it was important to take action in order to make the world a better place. When I was in my twenties, during the military junta, I became a member of the Lambrakis3 resistance youth group, so as an opposition member I had to report to the police every Saturday. When my situation became unsustainable, I was forced to flee the country through Yugoslavia with a false passport. I joined a travelling theatre company that was on its way to Germany to perform for Greek refugees living there. Before that, I had been studying at a drama school, which I almost finished, but then I received an invitation from my brother, who was already teaching at the Karl Marx University in Leipzig. His girlfriend was Brecht’s daughter Barbara, so I was invited to the Berliner Ensemble through her.

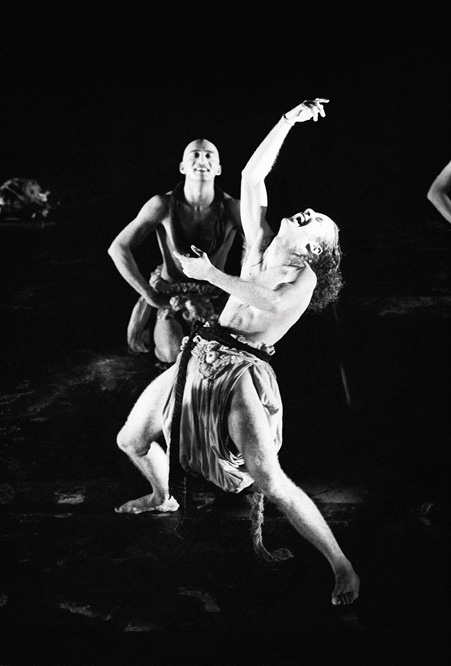

Figure 1. Bacchae by Euripides, Berlin 1987, Berliner Ensemble, Calliope Tachtsoglou, Akis Sakellariou, Sophia Michopoulou, Giorgos Symeonidis. Photo: Pierre Guillaume

Before we move on to the most important milestones in your theatre career, can you recall the moment when you first felt theatre was to be your true calling? When did you first feel the overwhelming power of the theatre?

■ In the village where I lived, from the age of seven, I was always the main character in the school celebrations, and I even helped the others, explaining to them how to play their roles. Even then I felt I had a very strong affinity with it, despite the fact that I had no developed theatrical vision and I had never even seen a single theatre performance. On Mondays theatre shows were broadcast on the radio, which I listened to with my mother, and it was through them that I first heard the voices of the great Greek actors. From then on, I kept asking about them, [and] went to the cinema, but only very rarely did I get to see theatre, only sometimes when a travelling company was performing. But when I moved to Katerini at the age of twelve, I was able to go to the theatre regularly, I went to Saloniki and other cities, and that’s when my ideas about theatre and acting really started to take shape. Eventually I decided that I wanted to do this for the rest of my life, as an actor, and a comic actor at that.

Choosing a career in the theatre was a deliberate choice, but until you had a fully developed concept, were you equally deliberate in seeking out those you could learn from? Who do you consider your masters in your theatre career?

■ Indeed, I looked for the masters from whom I could learn the most, who were the most inspiring to me. I consider Manos Katrakis to be one of my first masters, and when I entered a drama school in Athens (the Drama School of Kostis Mikhailidis, 1965–67 – A. K.), I was already assisting my teachers in their productions. At that time I didn’t think I was going to be a director, I was more interested in being an actor, and as a student actor I had already played small roles in musical theatre performances and comedies. As soon as I stepped on stage, everyone burst out laughing, but after a while it bothered me more and more and I thought I didn’t want to be just a comic actor, one of a dozen. For instance, Beckett was much closer to me, and it didn’t fit at all with the style of play that was typical of the entertaining type of commercial theatre. And then I received an invitation from my brother in Germany, but despite my desire to go there, I couldn’t get a passport because of my left-wing sympathies. So I had to get a forged passport to leave the country. Then in Amsterdam I left the theatre company and contacted my brother on the phone, who put me in touch with the Patriotic Anti-Dictatorship Movement. This organisation helped me travel from Germany (West Germany – A. K.) to Sweden, where I was able to join the Royal Swedish Theatre through connections with relatives and friends, and work as one of Ingmar Bergman’s assistants for about two months. Bergman was directing Hedda Gabler at the time, and for me it was the first encounter with an outstanding director, a great artist. During this time I had my visa for East Germany ready, so I could finally travel to Berlin to join the Berliner Ensemble. I remember my brother waiting for me at the train station, and we met again after twenty-five years, as he was one of those who had been repatriated from the dictatorship to various socialist countries as a child. And from that point on, a different and very exciting life began for me.

The morning after my arrival, I was terribly excited to go to Brecht’s theatre. Around half past seven an old lady was walking just in front of me, and I followed her to the theatre. When I entered the theatre cafeteria, someone came up to me and said that Helene Weigel, the theatre’s director, and Brecht’s wife, was waiting for me. When we met, she turned out to be the old lady I had been following and thought was a cleaning lady. After that, I became close to a great many people, including Ekkehart Schall, one of the greatest actors in Brecht’s company and the leading actor in his productions, and Heiner Müller, the theatre’s dramaturge, who later became my mentor and master, but I also met many other important actors and artists. Ultimately, they were the ones who shaped me, because I went there with a lot of ideas and thoughts, but I was in a kind of “Mediterranean chaos”. I couldn’t really control my wide-ranging, sprawling imagination because of my passionate, Mediterranean temperament, and it was there in Germany that I understood that I had to build a system, and develop a method of working. I was fortunate to have teachers from an early age who were important artists, such as a Chinese master from Shanghai, from whom I learned a lot about the interpretation of time, or Ekkehart Schall, who was also an excellent juggler and worked systematically on developing his diaphragm by packing iron plates on his stomach, or the renowned set designer Karl von Appen. But first and foremost, I must talk about Heiner Müller, to whom I owe most of all. When I first arrived in Germany from Greece, I was mostly influenced by Max Reinhardt, believing in a more “classical” approach to theatre. But, strangely enough, it was Heiner Müller who led me to the deeper essence and philosophical significance of my own classical, ancient theatrical heritage, and this was far from a neoclassical or romantic understanding. In other words, he did not make me see the ancient heritage from the perspective of Schiller or Goethe, but rather from a kind of theoretical, neo-Marxist point of view, although he was also a serious critic of Marxism in later years. Heiner Müller, who joined the Berliner Ensemble in 1972, felt that there was a crisis, a strong opposition between the company and Brecht’s legacy, and suggested a new approach. Brecht actually influenced me through Heiner Müller, and it was through him that I came to a new interpretation of classical Greek tragedies. Our acquaintance began in a rather strange way: in the canteen I saw a man in the evenings who often got drunk. Once he asked me where I was from. To my reply, he simply said, “Ah, Greece? I am just writing a play about Medea”. Then he invited me to his place. The very next day after my visit, I knew that he would be my master. He first read Medeamaterial to me, and later also The Liberation of Prometheus, which I staged in Berlin some twenty years later, in 1991, with Heiner Müller himself playing the role of Prometheus. I consider him my real master; later we became friends, and he visited me several times in Greece. I think that there were real masters then, and a master-student relationship really existed. Today, many people prefer to learn through YouTube, and the learning process has changed a lot. After my years in Germany, I returned to Greece and started to go my own way, which proved quite difficult at first. I set up a small theatre group, a creative workshop, with which we began to look for a completely independent language of form.

Why did you decide to return to Greece? Would you have had the opportunity to continue working with your master in the famous Berliner Ensemble?

■ During the military junta, I had no opportunity to return to Greece, but as soon as the dictatorship ended, I wanted to go right back. But Heiner Müller himself and Matthias Langhoff were always urging me to stay, saying that I would have a great career in Germany. But I didn’t see the point, I felt I had to go, and a career was possible without staying in East Berlin. My ways didn’t really fit the German mentality anyway. Of course, this was not the case with Müller and his circle of friends, such as Castorf, with whom I had a very good relationship, and I considered them my role models because of their philosophical and literary work, but at the time there was a euphoric, celebratory mood in Greece because of the end of the dictatorship, and I felt somehow caged in Germany. My severe homesickness obviously played a part in this.

Returning to Greece a whole new era has begun for you. Did you have to rebuild your theatrical existence or was this a continuation of the journey you had already started?

■ It was more of a continuation, as people were waiting for me, many of them hoping that I would return. Back home, they knew about my experience, the Brecht seminars I had held, my relationship with Heiner Müller, so they welcomed my arrival. I moved to Saloniki, and there I founded a company, whose members later became very famous actors. I took over the management of the Drama School of the State Theatre of Northern Greece in Thessaloniki, where I was director between 1981 and ’83. I was also co-chair of the theatre’s cultural committee. I staged Lorca’s Yerma and Brecht’s Mother Courage, which was a huge success, but after a while I got fed up with the cumbersome nature of public theatre and decided to hit the road and just travel the world for a year. From New York to Shanghai and Tokyo, I had an incredible variety of experiences. In Tokyo, for example, I met Tacumi Hijikata, the founder of Japanese butoh dance. These experiences were very important for me, because I wanted to reinterpret myself, the theatre, everything that seemed obvious before.

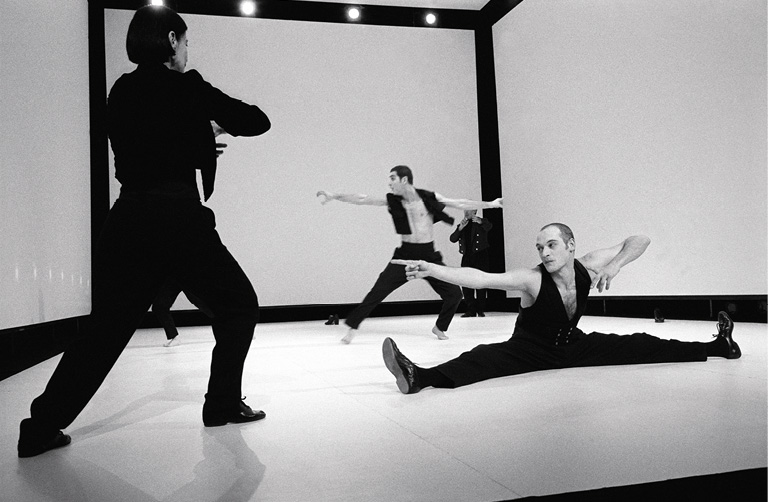

Figure 2. Dionysus based on Bacchae by Euripides and pre-Colombian myths, Bogota 1998, Teatro de la Casa, Jorge Ivan Grisales. Photo: Johanna Weber

During your performances at the State Theatre, did you apply the actor training method that you have since developed in detail and which forms the basis of your later work and educational work?

■ I first started using it when I was directing Yerma, because I didn’t see it as a dramatic work, but as a tragedy. In fact, from the end of the ’70’s onwards, I turned increasingly towards ritual theatre, partly under the influence of Brecht, but mostly because of an inner urge and interest. This probably reflects the influence of my origins and the cultural experiences and oriental traditions I carry. This was already very evident during the staging of Yerma, which was like a ritual choreography. During the preparation, I gave the actors a training session, which I had learned from my Chinese master. It was, of course, different from what I have been doing for almost forty years now, but it was a very positive experience for the actors and it had a significant impact on the quality of the performance. I myself have studied classical ballet for eight years, as well as Martha Graham’s dance technique [and] the Alexander Technique, I have worked a lot on my own body, and I have also studied the traditional rites of Northern Greece. I have danced on burning embers myself, I have tried many dangerous things. I underwent a lot of these bodily experiences and began to incorporate them into a system of my own, based on breathing. And over the years I gradually developed an individual training method.

Did you develop your training method entirely on your own, or was its incorporation into the system already linked to the creation of the Attis Theatre Company?

■ You can’t work alone in the theatre. There is always you and the material you are working with. If we consider the actor as material, we have to conduct thorough research first in order to build up a solid theoretical system. If you meet actors who work from routine, who build on stereotypes, and you simply put them side by side, you can only create schematic forms. I often experience this, but it makes a difference how open this material is to change and development. We should not be content to let the actor remain mere material, only reproducing stereotypes. It is important to wake him up to the need for change. I had this intention in mind when I founded the Attis Theatre, and since then I have created some 2,300 performances around the world in this spirit.

What do you see as the fundamental difference or similarity between Brecht’s theatre and the tragedy towards which your theatrical path has moved?

■ Brecht has nothing to do with tragedy, at most we can discover it in the structure of his plays. Just as in tragedy there is a dialogue and a chorus, so in Brecht’s plays the dialogue is usually followed by a song, which reacts to the previous dialogue and prepares the next. Perhaps that is all there is in common. But Brecht draws from society and speaks to society, so in that sense it is social theatre, whereas tragedy is a dialogue with God, so when I direct tragedy I am speaking to the gods and to people at the same time. The orientation is different, as in the case of Brecht the performance has a political message, a political “core”, whereas in the case of tragedy it is ontological. At the same time, it is much easier to discover a political dimension in tragedy than to find an ontological root in Brecht. Brecht always gives a social explanation and opens up a political dimension, and is more concerned with questions of human life, while tragedy turns towards the whole universe and asks a much deeper question, the ontological essence of existence. In this sense, Brecht sacrifices a lot on the altar of a presentation for society, although he could have gone much deeper if he had gone down to the ontological depths. In terms of structure, for example, his drama Galileo would have been suitable for this, or even his adaptation of Coriolanus, which is closer to tragedy in genre.

Compared to the strong politico-social approach of the German theatre, did the reinterpretation of Greek tragedies also represent for you a kind of intellectual-spiritual paradigm shift towards a more universal, “vertical” oriented theatrical language?

■ This orientation has been present in me from the beginning, mainly through my family roots and upbringing, but also through my theatre studies and work, and my encounters with the great masters also guided me in this direction. Gradually, I came to the realisation that I must always look upwards, that I must move upwards. I could describe this shift with Hegel’s dialectical concept of Aufhebung4, which is a very beautiful, philosophical expression, a capturing of a paradoxical idea. After the statement comes the denial of the statement, and then “denying” it, we come to another, different kind of statement. This concept expresses man’s aspiration to always rise above things, phenomena, and to deny something in such a way that he thereby also moves to a higher spiritual level.

And this spiritual progress, this new stage in your career, is marked by the creation of the Attis Theatre, which you founded in 1985.

■ Indeed, the founding of the Attis Theatre thirty-seven years ago marked the beginning of a new era, the first step on this journey. Yes, in three years we will celebrate its fortieth anniversary!

The name of the company, Attis, is also revealing, as it draws from ancient Greek mythology.

■ The name was a conscious choice on my part, as Attis is the Phrygian version of Dionysus. I decided a long time ago that I wanted to work with Greek tragedy, and specifically with the Bacchantes and Dionysus, who is the god of theatre [and] of metamorphosis, but we could also call him the god of strength and energy. He is the one who connects and unites people with nature and other gods. I wanted to enter into the study of this, into this spiritual force field, so I turned to the Bacchantes. I spent a year honing and developing my training method, the method I have used to prepare the actors to work on the stage. When I talk about training, I am talking about a very well thought-out, systematic physical exercise regime, which is also unthinkable without a certain intellectual-philosophical background. As in medicine, the practitioner must have an elaborate scientific system behind him, otherwise he is not a doctor, but a charlatan. Thus, each practice or set of practices has a detailed explanation, a scientific basis.

On the one hand, the system of operation of the Attis Theatre is based on the training method you have developed, on a rational, scientific basis, but when you say that theatrical creation has started on a particular “Dionysian” path and that “tragedy is in dialogue with God”, can we assume that there is a spiritual or even mystical experience behind this?

■ This path is a conscious decision on my part; there is nothing random about it. Because nothing happens by chance. And when I speak of God, I do not mean the Christian entity in the mystical sense. In fact, I don’t give him a face or any particular character. By that I mean the power above us. Ascension, or transcendental orientation, for me is a state of seeking God.

Figure 3. Heracles by Heiner Muller, Athens 1997, Attis Theatre, Sophia Michopoulou, Ieronymos Kaletsanos, Giorgos Symeonidis. Photo: Johanna Weber

You mentioned earlier your Eastern roots, the experiences that are linked to the Eastern tradition. An important part of this tradition is the inner journey, the metaphysical experience of being.

■ When I used to dance on burning embers during fire dancing rituals, my body was in a state in which my feet didn’t burn from the heat because I was in a state of trance that protected me from it. I noticed that when I was in this state, the control of the brain was reduced, that is, it was not my brain that was controlling my body. I jumped into the fire and my feet didn’t burn while dancing. It was the result of an ecstatic state, but I wouldn’t call it mystical or diabolical. My blood circulation was probably accelerated, so my own temperature was heated up, I would say, to a “Dionysian” temperature. For the blood in my body, which circulated at an accelerated pace, is the wine of Dionysus himself. Of course, there are many other ways to describe or explain this phenomenon. But one thing is for sure, if you put your cold foot on the fire, you will get burnt.

The Attis Theatre’s first and one of their most significant productions to break into the theatre scene was The Bacchantes, and it marked the beginning of the company’s journey, now several decades in the making. As I understand it, you vowed at the time to stage this production not once, but seven times. To whom did you make this vow and why seven times?

■ That’s right. This is my sixth production at the National Theatre in Budapest. And the seventh will be either in Senegal or in Yakutia, in the form of a ritual play in the forest. And I have made my vow to Dionysus, and I have done it seven times because it is a magic number.

How are the six versions of The Bacchantes born so far different from each other?

■ The first performance was still “virgin”, that is, formally pure. And the costumes were in an oriental style, so it was a kind of oriental version of Greek tragedy, but I was already relying entirely on the method I had developed in creating the production. The second version was staged during the US invasion of Afghanistan, with the Bacchans looking like the Taliban and the palace evoking Germany’s first industrial era. The set designer was Jannis Kounellis, an important representative of the Arte Povera art movement. This performance was produced in 2002 by the Schauspielhaus in Düsseldorf, starring prominent actors, and took place in a Siemens factory building, where Hitler and his men were preparing to build the atomic bomb. And the third show I directed in Colombia, with the participation of shamans and anthropologists as actors, and most of it was produced in villages in the Amazon, around Cauca Selva, where we were researching the ancient traditions of the indigenous tribes there. I myself participated in these rites, and later wrote about my experiences in a separate book. It was an extremely interesting and liberating experience for me, an inexhaustible, boundless, and profound feeling. It was quite fascinating to experience this depth of consciousness. The fourth version was created in 2015 at the Stanislavsky Theatre in Moscow, where I was invited by the new artistic director Boris Yukhananov. In the completely renovated and transformed theatre (which was then called the Stanislavsky Elektrotyeatr – A. K.). I chose the cast from about four hundred young actors, but excellent older actors also played there, who always had the spirit of Stanislavsky hovering over them. What made this performance special was that it managed to find a balance between tragedy and the style of Stanislavsky’s first period, which, for example, was represented by Maria Lilina at the time. It is no coincidence that Eisenstein also mostly called on Stanislavsky’s actors for various roles. In this production, Dionysus was played by a woman, Yelena Morozova, one of the most prominent Russian actresses of our time. It was an extremely physical and crazy performance. My fifth production was in Taipei, Taiwan, organised by the National Theatre there, and it was the largest production of its kind ever, with a cast of about sixty and with the involvement of a legendary drum ensemble, the Ten Drum Art Percussion Group. Alongside the actors, it featured thirty-five dancers and huge drums. A special open-air venue was set up between the palace buildings, and around two thousand spectators sat on the steps of the old palaces to watch the performance. At my special request, the performance featured a chorus of women from an indigenous minority in Taiwan, who resembled Filipinos or Papuans. The final result was shocking, the presence of the choir almost shocked the audience, and the actor playing Dionysus was in an almost frantic, mad state, producing a very extreme presence. I staged the sixth performance here in Budapest, at the National Theatre, but I didn’t really have a choice of actors, so I accepted the theatre’s proposal. But I have to say that I can work with great actors, and I feel that I have found a good rapport with all the actors, including the student actors in the chorus and supporting roles, who have been through two months of hard training. I think the end result is an extremely powerful piece.

One of your most important writings, The Return of Dionysus, which was published in 2015, has been translated into around twenty-five languages. Can we consider it a kind of summary of your work to date, an intellectual and theatrical ars poetica?

■ Yes, in a sense you could call it that. It will be followed by another one, The Song of Dionysus, which is mostly about voice, the use of voice.

Reflecting on the title of your book, why should Dionysus return? Because it means that he has disappeared from our world. Why did he disappear and why is he returning now?

■ On this question, in 2011 a three-day symposium was organised in Berlin, chaired by Erika Fischer-Lichte and based on my theatre work, entitled Dionysus in Exile5. This has led to some excellent writings, mostly interpreting the disappearance of the Dionysian spirit. I believe that Europe was the first to expel him, and put Apollo in his place, focusing on the idea of beauty and harmony. This approach also influenced the ideology of National Socialism later on. Three volumes on the subject have been published so far, one of which is Journey with Dionysus6, in which several major theatre thinkers, including Hans-Thies Lehmann, write about my work, and the other Dionysus in Exile7, while the third is the Return of Dionysus8, in which I explain my training method in detail. As we live in an age in which we have lost our voice, lost our energy, lost our physicality, and technological developments have erased everything, perhaps his return could be the solution. We can rediscover him, [and] our senses, [and] learn to hear again, because today we can no longer hear our world and each other, we are almost deaf. So that we can see again, because our vision has been distorted, and so that we can speak again, because we are mute. So that we can think again, because we have become dumb, so that we can grasp things again, because we are unable to do that today. Dionysus embodies all of this, and it is something that is sorely lacking in theatre and in life today. Gone is the tradition of lamentation, which is a very important aspect of our existence, the capacity to mourn. Also, a true expression of joy, of ecstasy. We have to experience all this again to become human again. I would say that Dionysus is the liberating force and the force that creates Man. Once, before one of my performances, I wanted to put a microphone on stage, but that night I had a nightmare, Dionysus appeared in front of me to literally kill me. Then I understood that I had to throw away the microphone and let the natural human voice prevail. What I mean by that is that I have a very direct, strong relationship with Dionysus, both in life and in the formal language of my theatre. As I said, for me he is the creator of Man. Of course, this form varies somewhat from performance to performance, but I always keep the natural basics of theatrical expression. I never use video feeds or microports, for example. With actors, I tend to try to open up their voices and struggle for months to get them to speak in their own voice. In fact, that’s the vow I made to Dionysus, to put my art at his service.

You have directed and taught in countless places around the world. What is your experience, how open are actors to this Dionysian approach in their theatre work?

■ They are absolutely open. I would say that when Dionysus opens the door for them, they rush to enter. This is the Dionysian material. It frees us from the bonds of psychologism and moves us towards natural existence, towards inner vision. For example, when twelve actors breathe on stage at the same time, there is nothing more powerful and natural in the world. And this is captivating for the actors, almost therapeutic, calming them down, bringing them back down to earth. I am always delighted when, anywhere in the world, not only young actors but also older, experienced actors, up to seventy or eighty years old, come across this new thing and throw themselves into it with great enthusiasm because they are not afraid to experiment.

During our conversation, we have already talked about the masters who have started, shaped and inspired you throughout your life. How do you see you can pass on your knowledge as a master and will the theatrical journey of Dionysus’ return continue in your students?

■ Yes, definitely. Savvas Stroumpos9 is the most important representative and teacher of this theatrical path and of course all my actors, but he is the one who most responsibly continues this spirit and method. He himself has trained some forty teachers worldwide, and my method is taught in various schools and theatre academies. For example, at the Moscow State College of Dramatic Arts, or in China, where this is taught to second-year acting students eight hours a week, but there are also teachers in Seoul, Berlin and Italy, there is actually a network of teachers. When a symposium on my work was held in Delphi, our students gathered there, but also Anatoly Vasiliev, Eugenio Barba, the Rimini Protocol and many others came to see a six-hour demonstration of our method. One of the reasons why this was fantastic was that our students spoke different languages, Chinese, Korean, Italian, Portuguese and Russian, yet they were all from the same school. Our teachers are invited to many countries to give training and workshops. The results are fast and spectacular because it opens up the voice and energy of the actors. Of course, there have been repertory theatres where this kind of method did not fit with the established acting presence, but, for example at Beijing State University or in Istanbul, there are special departments dedicated to my method and Tadashi Suzuki’s method. I have many followers and I am glad that more theatres want to learn about the method, because it can help educate the next generation of theatre makers. The forty teachers we train come to Greece every summer to attend a month-long seminar and it’s a wonderful feeling to see them improve year after year. It is interesting to note that in this respect the English theatre is a rather closed medium, because Shakespearean theatre dominates there.

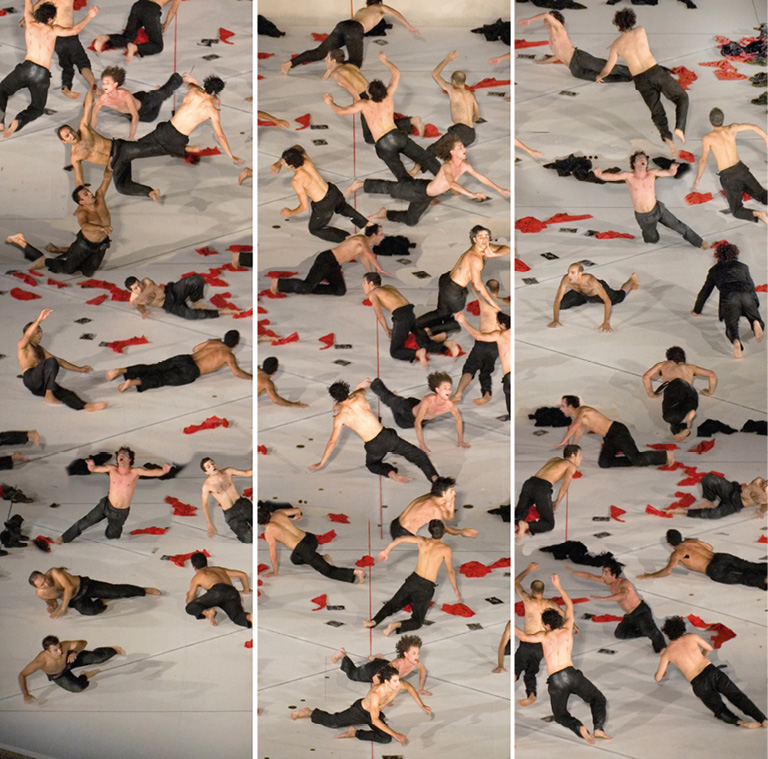

Figure 4. Persians by Aeschylus, Epidaurus 2006. Ancient Theatre, Chorus. Photo: Johanna Weber

In addition to ancient Greek tragedies, you have also staged works by other authors. Which of these do you consider the most important?

■ Indeed, it is important to clarify that my work is not only related to Dionysus or ancient Greek tragedy. I have been commissioned by theatres and international festivals all over the world to direct productions based on works by Brecht, Beckett, Heiner Müller and others, some of them several times. My important works include Mother Courage by Brecht, Endgame by Beckett, and Medeamaterial, Quartet and Mauzer by Heiner Müller. I have also staged many new Greek works in Greece, introducing many new writers and poets to audiences, who have become very successful through this. They also reflect my approach to tragedy, because for me this is the basic principle of theatre, which can give even a small performance a large format, [making it] able to expand and open up the energies inherent in the text. Such as Amor or Alarme, which were also presented at MITEM.

In addition to your directing and theatre pedagogical work, the creation of the Theatre Olympics, which you initiated in 1995 in Delphi and which has since grown into one of the largest theatre gatherings in the world, is of particular importance. Was this impressive event born specifically as an outgrowth of your artistic quest, or more out of a need to shape society and create community?

■ This clearly came out of my work in the theatre, my artistic quest, because I wanted to dig as deep as possible in understanding and experiencing tragedy. My desire was to get to the heart of tragedy. So in 1984, I organised a theatre forum in Delphi, to which I invited the most important creators of the theatre world. Among the participants were Andrzej Wajda, Robert Wilson, Heiner Müller, Dario Fo, Tadashi Suzuki, Jan Kott, [as well as] many prominent philosophers and artists, the cream of the artistic world of the time. We talked about why we should get together regularly and do a theatre event together. I first discussed this publicly with Tadashi Suzuki in 1986 in Tokyo, on Japanese state television channel 1. I made this proposal and asked Suzuki to be my partner and collaborator in this. Then I invited other renowned artists to collaborate, and the idea grew into a serious theatre forum, in which we discussed the crisis of theatre, [and] the crisis of art, with prominent personalities. This creative restlessness would not have led us to create a festival, nor was it planned, but we simply wanted to tell the truth about the state of theatre art and theatre education and to formulate new creative principles. I invited Eugenio Barba, Anatoly Vassiliev, the founders of La Mama theatre, Richard Serra and many other renowned artists. A late-night discussion developed, which I chaired, and that’s when we decided to create a large theatre meeting. The second question was where to get the money from. Together with Tadashi Suzuki, we went to Japan and managed to get the mayor of Sizuoka city to support our initiative. In Sizuoka, which is an industrial city, they were going to build a whole section of the city for this purpose, based on the design by a famous Japanese architect.

I took these plans to Melína Mercuri10, the Greek Minister of Culture at the time, and I told her that the Japanese would like to organise the first Theatre Olympics, but that in my opinion it should be launched in Greece. She supported my initiative and thanks to her we organised the first Theatre Olympics in Delphi in 1995, which was a huge success. In the presence of around five hundred journalists, we announced the manifesto of the Theatre Olympics, and Juan Antonio Samaranch11 gave us permission to use the word “Olympics”. Japan then hosted the second Olympics in 1999, followed by Moscow, Istanbul, Seoul, Beijing, Wroclaw, Delhi, St Petersburg and Toyama. The Theatre Olympics have grown into an event of huge significance, which deserves a separate discussion. The history of the past twenty-seven years is extremely rich and varied, and we would like to capture this in a well-prepared and documented book following the year 2023 Hungarian Theatre Olympics.

1 The Pontic Greek language or Pontic language (or the more Latinised form Pontus is also used) is a variant of the Greek language originally spoken in the Pontic region of northern modern Turkey. As in other varieties of Greek spoken in Asia Minor, Turkish, Persian, and Caucasian influences are also apparent in Pontic. Due to population exchanges following the First World War, the speakers of modern Pontic are mostly resident in Greece

2 Trabzon (also referred to as Trapezunt) is a city in the northern part of Turkey, on the Black Sea coast, the capital of Trabzon province, and the centre of the district of the same name. It was founded in the 8th century BC.

3 Grigoris Lambrakis (1912–1963) was a Greek politician, physician, athlete, and professor at the University of Athens Medical School. He was a member of the Greek resistance against the Axis powers during the Second World War and later became a prominent anti-war activist. His assassination by right-wing activists sparked mass demonstrations and led to a political crisis in Greece.

4 “Aufhebung” or “Aufheben” is a German term that has several seemingly contradictory meanings, for example, “to lift”, “to abolish”, “to interrupt”, “to suspend”, “to preserve”, “to surpass”. In philosophy, the term Aufheben is used by Hegel in his exposition of dialectics, and can be understood in English as “to preserve by eliminating”, or “to exceed”.

5 Between the 23rd and the 25th of September, 2011, the Hellenic Cultural Foundation in Berlin presented “Dionysus in Exile. The theatre of Theodoros Terzopulos.” The theatre of Theodoros Terzopulos, an international symposium brought together scholars and researchers from the fields of theatre studies, classical philology, psychoanalysis, psycho- and neurolinguistics with writers, dramaturges, directors, and actors to share their views on the specific characteristics of Terzopulos’ theatre, and its Dionysian character.

6 Raddatz, Frank M Reise, ed. 2006. Journey with Dionysos: The Theatre of Theodoros Terzopoulos. Berlin: Theater der Zeit.

7 Raddatz, Frank M Reise, ed. 2019. Dionysus in Exile: The Theatre of Theodoros Terzopoulos. Berlin: Theater der Zeit.

8 Raddatz, Frank M Reise, ed. 2020. The Return Of Dionysus: The Method Of Theodoros Terzopoulos. Berlin: Theater der Zeit.

9 Savvas Stroumpos (1979–) is a Greek actor, director and theatre pedagogue. He graduated from the Drama School of the National Theatre of Greece in 2002. In 2003, he obtained an MA in Theatre Practice from the University of Exeter (UK). Since 2003, he has been working as an actor at the Attis Theatre and as assistant to the director Theodoros Terzopoulos.

10 Melína Mercuri, Latin transliteration: Melina Mercouri (1920–1994) Greek actress, singer, politician, member of the Greek Parliament, first female Minister of Culture of Greece from 1981–89 to 1993–94.

11 Juan Antonio Samaranch Torello (1920–2010) Spanish sports diplomat, known worldwide as the 7th President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC).